In rescinding its pilot Expedited Permit Review Services Program last week, the Coral Gables City Commission halted a modest attempt to modernize a permitting process that many in the private sector find opaque and unnecessarily slow. But the 3–2 vote did more than reverse a single initiative—it sidestepped a broader opportunity to address a chronic issue affecting homeowners, business owners, and city staff alike.

The proposal, introduced by Commissioner Melissa Castro, aimed to streamline review times for a specific category of projects: interior remodels of residential and commercial properties. It offered applicants the option to pay a 15 percent premium in exchange for a guaranteed five-day turnaround per review cycle. The plan was not a wholesale rewrite of policy. It was a pilot—limited in scope and designed to test the city’s ability to deliver faster service without compromising standards.

Rather than evaluate the results of this approach or offer improvements, three members of the commission voted to terminate it outright. Mayor Vince Lago, Vice Mayor Rhonda Anderson, and Commissioner Richard Lara offered little discussion. Some cited concern over fairness; others claimed to support the concept but opposed the politics surrounding it. Yet what went conspicuously unspoken was any commitment to pursue an alternative path forward. They scrapped the pilot and provided no recourse in its place.

That omission matters. The permitting process in Coral Gables may be rigorous by design, but rigor and inefficiency need not be synonymous. High standards—such as those that protect the city’s Mediterranean architectural heritage—can and should coexist with clarity, transparency, and timely execution. Residents and professionals have the right to expect permitting that reflects the city’s values not just in what gets built, but in how those decisions are made.

The commission’s role is to steward progress. On this issue, it failed to lead.

Instead of a deliberative review of what worked or didn’t work in the pilot, the majority opted for rejection. No motion was made to study the program’s outcomes. No task force was proposed. No acknowledgment was given that the existing system frustrates residents and professionals alike. The action spoke volumes: better to erase an opponent’s initiative than improve upon it.

To be clear, the pilot was imperfect. Concerns about equity, implementation logistics, and communication were valid. But those are the kinds of problems that pilots are meant to surface—and solve. Ending the program without exploring what could have been learned from it is not just premature. It is shortsighted.

The commission now has a choice: continue a path that rewards political gamesmanship or shift toward constructive problem-solving.

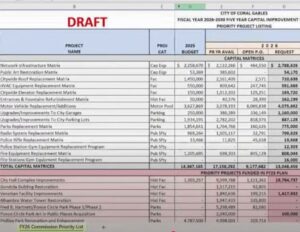

One place to start is with data. A comprehensive audit of the permitting process would identify where delays are most common and which applications generate the most confusion or complaints. Another step is stakeholder engagement. A task force that includes residents, architects, contractors, and staff could surface practical reforms—such as pre-approved design templates for common improvements, better digital tools for applicants, and clearer timelines.

These ideas are not novel. Cities across the country with equally stringent planning codes have implemented them to reduce bottlenecks and build public confidence in their permitting systems. Coral Gables can do the same.

Equally important is cultural reform. The permitting process should not feel adversarial. Applicants should encounter a system built on predictability and service, and staff should have the training and tools to uphold the city’s standards efficiently and respectfully.

By eliminating the expedited option without replacing it, the commission sent a signal—one of resignation, not reform. And the public has noticed.

To those who follow city politics closely, the dynamics at play were unmistakable. The majority who voted to scrap the pilot did so without offering a substitute solution. That is not governance. That is retribution. Maybe their reasons were better than they let on. Maybe they will adopt some of the reforms outlined above in future meetings. If so, the community will welcome that shift.

But if they don’t—if weeks or months pass without serious proposals to address the underlying issues—then it will be hard to argue that their motivations were anything other than political. And if they are willing to bury good ideas simply because of who proposed them, what else will be discarded next?

Good governance is not measured by who wins a vote. It’s measured by what a city gains in the process. In this case, Coral Gables gained nothing.

The permitting problem won’t fix itself. It will take data, transparency, public input, and, above all, political will. The commission should return to the issue with the seriousness it deserves—and demonstrate that it is capable of leadership that rises above the grievances of the past.

Until it does, residents and businesses are left with a system that needs improving and no sign that help is on the way.

This Post Has 2 Comments

“And if they are willing to bury good ideas simply because of who proposed them, what else will be discarded next?”

That is the crux of the matter. Anything not proposed by Lago, Anderson and Lara will be discarded. As stated in the editorial, this was retribution. Vindictive shortsightedness which ignores the needs of the residents. Blatant political gamesmanship.

In emails to residents Lago claimed that the problems in the permitting process were due to a lack of leadership for the past 2 years. While that is an excuse which doesn’t hold water because the inefficiencies and delays have been ongoing for years, this refusal to even consider the pilot program demonstrates the lack of leadership on the current commission. It’s a blame game, and Lago and Anderson don’t ever take the blame for anything, nor are they, together with Lara, helping find a solution to a longstanding, frustrating problem with city permits. They don’t give a damn about the residents.

What is REALLY stupid about the permitting process for a new home taking YEARS is that they are leaving huge amounts of property tax revenue on the table. If a $4 million house is completed in one year instead of three, that is over $100,000 of tax at the rates Miami Dade and Coral Gables extort from its residents.